I’ve heard this comment from innovation experts a few times recently and I am puzzled by it. I know many teachers (full disclosure – my wife is one) and without exception, they appear to be genuinely supportive of creativity in their classrooms. So, non-teacher creativity experts say that teachers don’t support creativity and teachers say they do. Who is right? A paper by Westby and Dawson (1), covering two studies of teachers attitudes towards creativity, goes a long way to explaining this apparent conflict.

In the first study, they asked a set of college students to rate fifty adjectives as to “how characteristic you think each of the following is of a creative 8-year-old child?” A set of teachers were then given a list of the ten highest rating and the ten lowest rating adjectives and asked to rate their favourite and least favourite pupils against each adjective on a nine-point scale. The results showed that teachers’ favourite pupils tended to show fewer creativity traits than the teachers’ least favourite pupils. This would appear to confirm that teachers do not like creative pupils in their classroom.

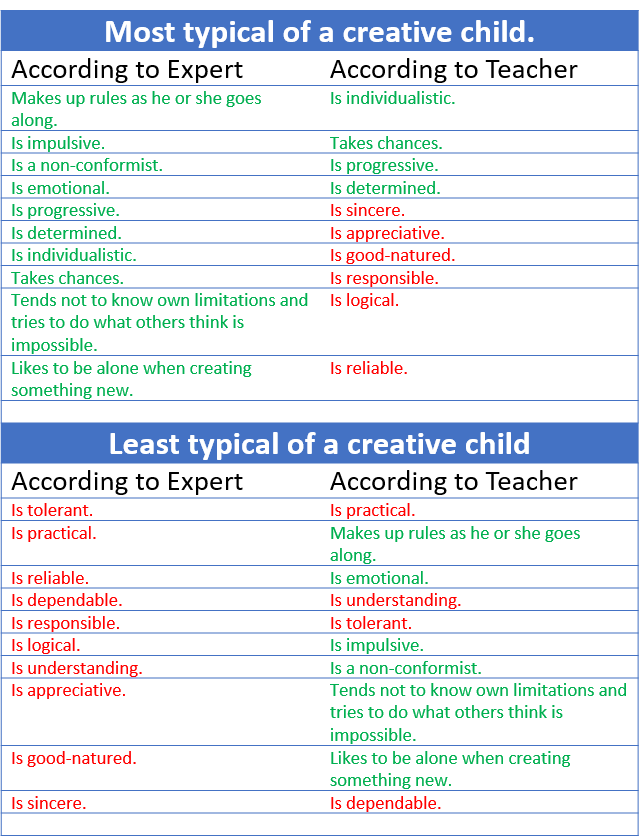

Not so fast. In the second study Westby and Dawson tried to explore the reasons for this. They gave the list of adjectives to teachers and asked them to rate them as to “how characteristic you think each of the following is of a creative 8-year-old child?” When the students in the first study did this, their ratings agreed very well with those of experts in the field of creativity. However, the ratings from the teachers were different. Table 1 shows the two assessments. Characteristics in green would normally be expected to be associated with creativity and characteristics in red would not. It is clear, even from a quick glance, that teachers have a very different model of creativity than “experts” in the field. For the following discussion, we will refer to these as the teachers’ model and the traditional model.

Comparison of Creativity Characteristics as Assessed by Experts and Teachers

In a second paper Westby and Dawson (2) probed the difference in the two models further and showed that the traditional model correlated well with creativity shown in a figural task (making a collage) but not in a verbal task (writing a short story). The teachers’ model correlated well with the verbal task but not the figural task.

These reports were based on studies of creativity in eight to ten year old children, but the results highlight some factors which may have more general importance. In particular, the teachers’ model does include some of the expected creativity characteristics. The other characteristics in the teachers’ model would normally be associated more with acceptance, or “fitting-in” than with creativity. There is also a hint of good teamwork. Similarly, the least typical characteristics in the teachers’ model which are misplaced (in the opinion of the experts) are those which are likely to cause friction between a pupil and his or her peers or between a pupil and the teacher. In essence, the results suggest that, in an organised situation, there is a conflict between creative behaviour and acceptable behaviour.

Westby and Dawson hypothesise the teachers’ model is one that makes it easier to manage the classroom but this does not mean that it is only to make life easier. One key component, that allows people to turn creativity into innovation, is the ability to sell the idea. Many of the characteristics in the teachers’ model are related to this.

There are three possible situations.

1. Creative employees become disillusioned and leave the company. We have all heard the stories of great entrepreneurs who left a company job because the company did not understand them.

2. The unacceptable behaviours are squashed and so the problems are eliminated, but so is creativity.

3. Some employees learn to change their behaviour while continuing to be creative. In effect, they adapt to fit the company’s culture, while still managing to be creative. To do this, they need to develop traits closer to the teachers’ model than the traditional model.

The third of these is exactly what is needed in a business setting. For a long time, we have heard companies complain that they need more “entrepreneurs” in their company. There is even a buzz word for this – “intrapreneurs”. However, in our experience, they quickly lose them again. Either they leave because they have become frustrated, or the company sacks them because it cannot tolerate their impulsive, self-centred behaviour. Companies need to learn how to encourage/train their creative employees to follow the third path.

Are the characteristics needed for successful creativity the same for a small entrepreneurial company as for a large multi-national? We would guess not. The traditional model is very close to most people’s perception of an entrepreneur – creative, progressive, determined, non-conformist and willing to take risks. These are useful qualities and it is these that most companies are referring to when they say they want more entrepreneurial spirit. Unfortunately, the entrepreneurs also come with their “dark side”. They can be intolerant, solitary and undependable. They often show disregard for authority and do not easily take advice. When it is their own company, or the company is small, they can probably get away with this. However, this dark side is what causes so many problems when an entrepreneur tries to fit into a company environment. Actually, a true entrepreneur probably would not try to fit in, expecting the company to adapt to accommodate him or her. In the wild, as it were, this dark side is probably essential for an entrepreneur to be able to cope with the challenges he or she will face.

In the teachers’ model, the positive elements of the entrepreneur remain, but the dark side is replaced with character traits that allow the creative person to adapt to their environment, making them more effective innovators in a corporate culture.

The existence of creative people who can adapt to fit their environment was recognised in the 1960s and was given the name “The Briefcase Syndrome of Creativity” because it was

“…closer, if you will, to the notion of professional responsibility than to the Greenwich Village Bohemian or the North Beach Beatnik.” (3)

The quote comes from a paper entitled “The Highly Effective Individual”. This is a clue to the importance of the teachers’ model to innovation in business. Without the personal characteristics needed to fit into the company culture, an innovator would find it difficult to get their ideas taken seriously.

1. Creativity: Asset or Burden in the Classroom? Westby, Erik L and Dawson, V L. 1, 1995, Creativity Research Journal, Vol. 8, pp. 1-10.

2. Predicting Creative Behavior: A Reexamination of the Divergence Between Traditional and Teacher-Defined Concepts of Creativity. Dawson, V L, et al. 1, 1999, Creativity Research Journal, Vol. 12, pp. 57-66.

3. The Highly Effective Individual. MacKinnon, Donald W. 7, 1960, Teachers College Record, Vol. 61, pp. 367-378.

For any problem, we need to find information (facts and figures) but every ...

In my last blog, I used a gardening analogy for problem solving. This gives ...

Perth Innovation has developed a web application, consisting of a set of ...

This is an advertorial that was published in the Winter 2016 edition of ...